Book Review: The Lost Cyclist

By Lynne Tolman

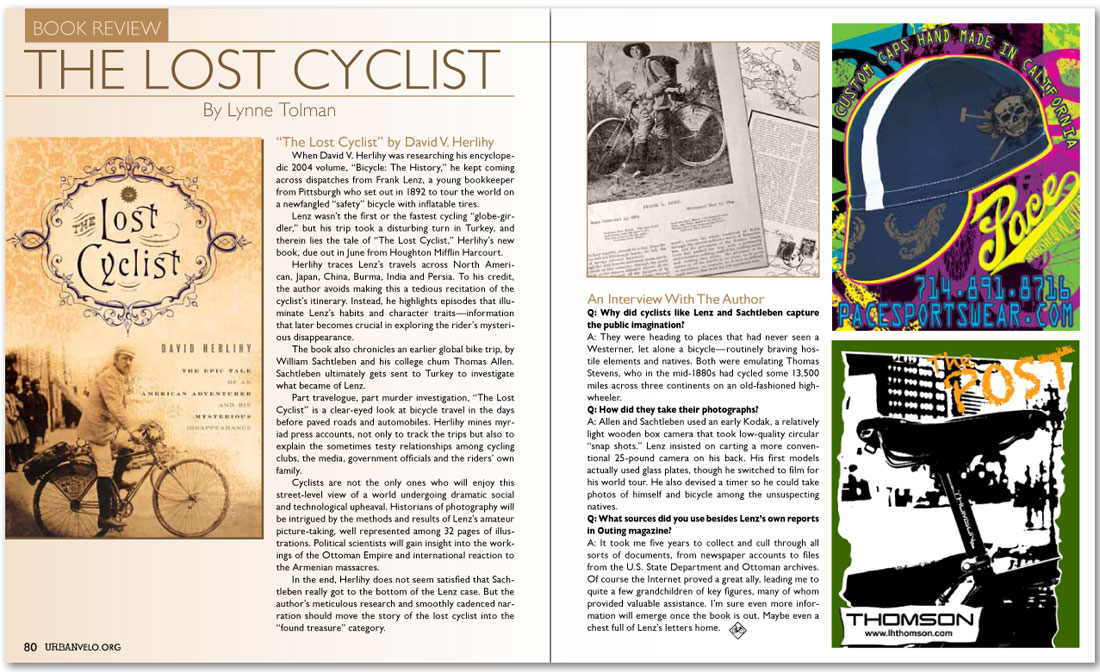

“The Lost Cyclist” by David V. Herlihy

When David V. Herlihy was researching his encyclopedic 2004 volume, “Bicycle: The History,” he kept coming across dispatches from Frank Lenz, a young bookkeeper from Pittsburgh who set out in 1892 to tour the world on a newfangled “safety” bicycle with inflatable tires.

Lenz wasn’t the first or the fastest cycling “globe-girdler,” but his trip took a disturbing turn in Turkey, and therein lies the tale of “The Lost Cyclist,” Herlihy’s new book, due out in June from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Herlihy traces Lenz’s travels across North American, Japan, China, Burma, India and Persia. To his credit, the author avoids making this a tedious recitation of the cyclist’s itinerary. Instead, he highlights episodes that illuminate Lenz’s habits and character traits—information that later becomes crucial in exploring the rider’s mysterious disappearance.

The book also chronicles an earlier global bike trip, by William Sachtleben and his college chum Thomas Allen. Sachtleben ultimately gets sent to Turkey to investigate what became of Lenz.

Part travelogue, part murder investigation, “The Lost Cyclist” is a clear-eyed look at bicycle travel in the days before paved roads and automobiles. Herlihy mines myriad press accounts, not only to track the trips but also to explain the sometimes testy relationships among cycling clubs, the media, government officials and the riders’ own family.

Cyclists are not the only ones who will enjoy this street-level view of a world undergoing dramatic social and technological upheaval. Historians of photography will be intrigued by the methods and results of Lenz’s amateur picture-taking, well represented among 32 pages of illustrations. Political scientists will gain insight into the workings of the Ottoman Empire and international reaction to the Armenian massacres.

In the end, Herlihy does not seem satisfied that Sachtleben really got to the bottom of the Lenz case. But the author’s meticulous research and smoothly cadenced narration should move the story of the lost cyclist into the “found treasure” category.

An Interview With The Author

Q: Why did cyclists like Lenz and Sachtleben capture the public imagination?

A: They were heading to places that had never seen a Westerner, let alone a bicycle—routinely braving hostile elements and natives. Both were emulating Thomas Stevens, who in the mid-1880s had cycled some 13,500 miles across three continents on an old-fashioned high-wheeler.

Q: How did they take their photographs?

A: Allen and Sachtleben used an early Kodak, a relatively light wooden box camera that took low-quality circular “snap shots.” Lenz insisted on carting a more conventional 25-pound camera on his back. His first models actually used glass plates, though he switched to film for his world tour. He also devised a timer so he could take photos of himself and bicycle among the unsuspecting natives.

Q: What sources did you use besides Lenz’s own reports in Outing magazine?

A: It took me five years to collect and cull through all sorts of documents, from newspaper accounts to files from the U.S. State Department and Ottoman archives. Of course the Internet proved a great ally, leading me to quite a few grandchildren of key figures, many of whom provided valuable assistance. I’m sure even more information will emerge once the book is out. Maybe even a chest full of Lenz’s letters home.