What started out as casual competitions spurred the formation of a community that has served as both a support and incubator of messenger and urban cycling culture. There was an early, informal stage from around ‘85 to ‘93, following the boom in the bike courier business in the 1980’s, where these races were happening with regularity and spontaneously as messengers would see one another on the street more and more, with the increase in employed couriers. Today pretty much everyone agrees that alleycats as we have come to know them—chaotic, fun, and more than a little dangerous—were born on the icy streets of Toronto.

In 1989 John “Jet Fuel” Englar, owner of Toronto’s Jet Fuel Coffee, dubbed his annual Halloween race the “Alleycat Scramble.” A few years later in 1992, German courier Achim Beier had the idea to hold a world championship event for messengers.

The next year, 500 messengers gathered in Berlin for the first Cycle Messenger World Championships, giving messengers from all over the chance to catch up, commiserate, race bikes and let loose.

This pivotal event served as a fertile breeding ground for sharing and spreading ideas, and the alleycat was a prime concept to be adapted in cities the world over. An “alleycat” came to be understood as a race held in live traffic, and when Toronto messengers took films of their races to the inaugural CMWC, it set off an enormous ripple effect throughout cities in every developed nation.

Just as wildfire can jump from branch to bush and leave untouched grass between them, the spark of the alleycat leapt from Toronto to Berlin to London and back to North America, to eventually course through the streets of every major city with a cycling presence.

London’s first true alleycat, held on open streets, came a few months after the 1994 CMWC. Putting in much of the work to make the second World Championships a success, “Buffalo Bill” Chidely and Boris Captain were too busy to actually participate in the CMWC events that weekend, so they took a trip to Toronto later in the year to be a part of the sixth annual Hellowe’en Alleycat Scramble—the event that had truly lit the fuse.

“It wasn’t linear in time or space,” Chidely wrote in Moving Target Vol 4 #3 (Spring 1995) trying to recap the Alleycat Scramble. “It was more like a riot than a race. Obviously, it had a beginning and an end. But in between... I have so many unanswered questions... It was complete and utter urban bicycle bedlam. It was the most fun I ever had on bike. In the cold light of the day, racing illegally at night, through a city centre is plain stupid. But when I was doing it I felt more fulfilled, more alive than I had since, well to be honest, I have never felt more alive. It was the biggest rush ever.”

About a week later, they threw the Andy Capp in London. Nine people showed up to race. “Boris, who had organised the race, was steaming mad that so few people made the effort,” writes Chidely in Moving Target in 2008, looking back on the race fourteen years later. “The week before Boris and I had been in Toronto for the 1994 Hellowe’en Alleycat Scramble, and there had been a HUGE number of riders. So to come back to our own city and see so few turn out was a little demoralising. But hey, London got there in the end.”

Squid, who started working as a bike courier in 1990 and is now the man behind Cyclehawk, first heard about CMWC when it was held in London in 1994. “It amazed me, the idea of it. The following year the championships were going to be in Toronto. I’d met some messengers from Boston who were planning on going; they offered me a ride up there, so I ended up going with them. The first time I ever heard about alleycats, and all that stuff was at the World Championships.

At the time in New York there wasn’t a big community. The only time messengers would get together would be for a memorial,” Squid says. “If someone got killed while they were working, so that was the only kind of group event I’d been to before the championships. Going to the Championships inspired me to throw my [first] alleycat.”

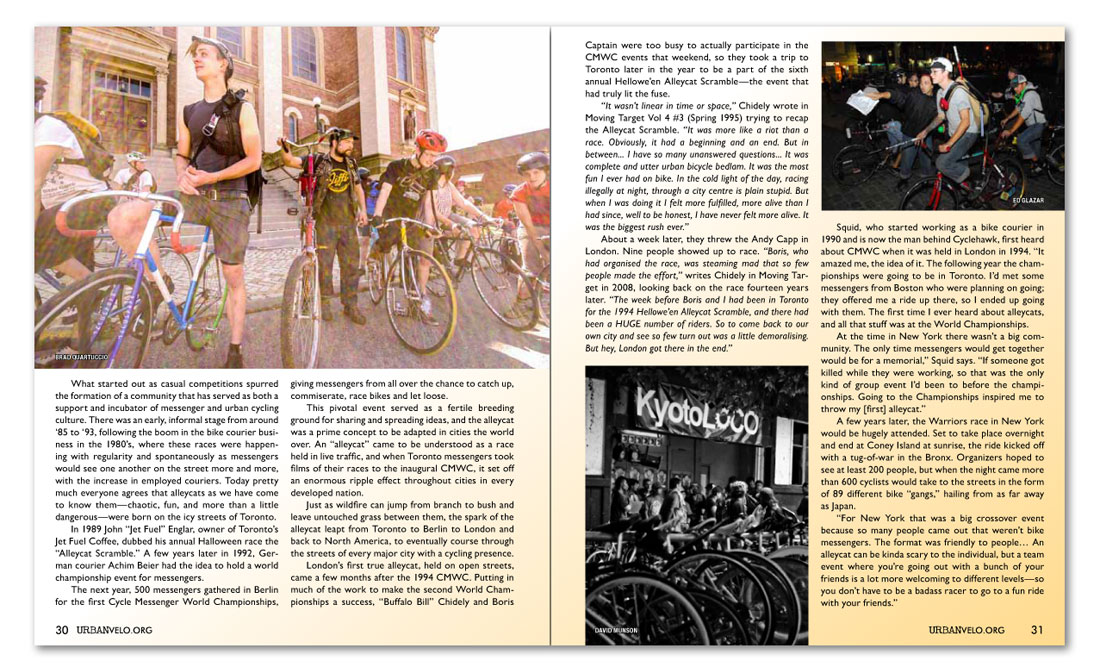

A few years later, the Warriors race in New York would be hugely attended. Set to take place overnight and end at Coney Island at sunrise, the ride kicked off with a tug-of-war in the Bronx. Organizers hoped to see at least 200 people, but when the night came more than 600 cyclists would take to the streets in the form of 89 different bike “gangs,” hailing from as far away as Japan.

“For New York that was a big crossover event because so many people came out that weren’t bike messengers. The format was friendly to people… An alleycat can be kinda scary to the individual, but a team event where you’re going out with a bunch of your friends is a lot more welcoming to different levels—so you don’t have to be a badass racer to go to a fun ride with your friends.”