I

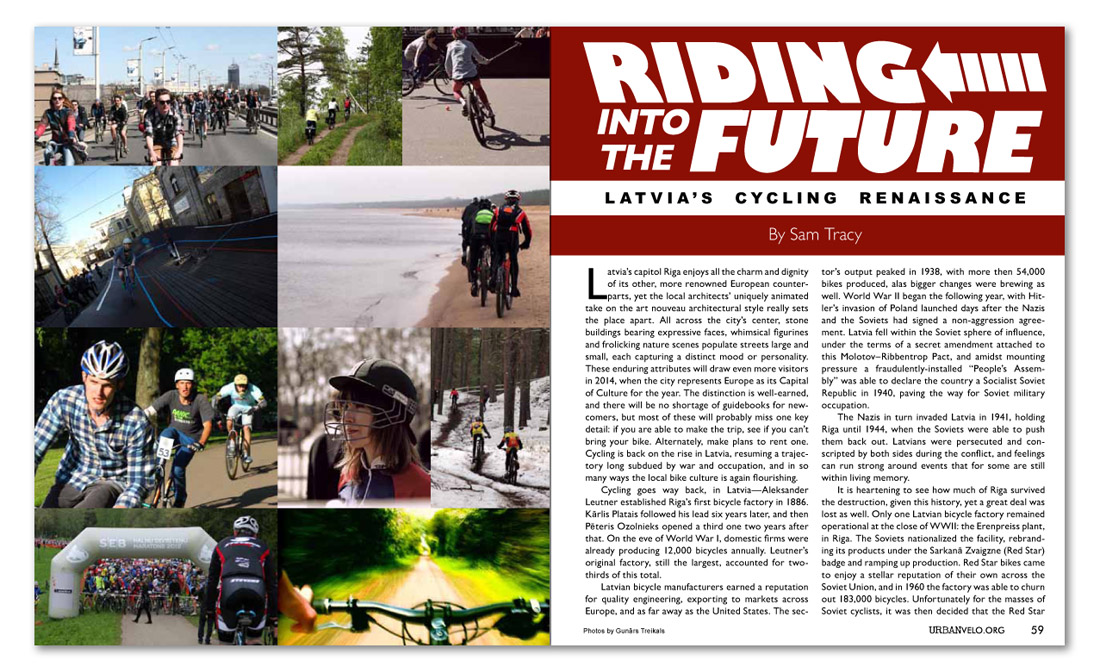

Riding Into The Future

Latvia’s cycling renaissance.

By Sam Tracy

Photos by Gunārs Treikals

Latvia’s capitol Riga enjoys all the charm and dignity of its other, more renowned European counterparts, yet the local architects’ uniquely animated take on the art nouveau architectural style really sets the place apart. All across the city’s center, stone buildings bearing expressive faces, whimsical figurines and frolicking nature scenes populate streets large and small, each capturing a distinct mood or personality. These enduring attributes will draw even more visitors in 2014, when the city represents Europe as its Capital of Culture for the year. The distinction is well-earned, and there will be no shortage of guidebooks for newcomers, but most of these will probably miss one key detail: if you are able to make the trip, see if you can’t bring your bike. Alternately, make plans to rent one. Cycling is back on the rise in Latvia, resuming a trajectory long subdued by war and occupation, and in so many ways the local bike culture is again flourishing.

Cycling goes way back, in Latvia—Aleksander Leutner established Riga’s first bicycle factory in 1886. Kārlis Platais followed his lead six years later, and then Pēteris Ozolnieks opened a third one two years after that. On the eve of World War I, domestic firms were already producing 12,000 bicycles annually. Leutner’s original factory, still the largest, accounted for two-thirds of this total.

Latvian bicycle manufacturers earned a reputation for quality engineering, exporting to markets across Europe, and as far away as the United States. The sector’s output peaked in 1938, with more then 54,000 bikes produced, alas bigger changes were brewing as well. World War II began the following year, with Hitler’s invasion of Poland launched days after the Nazis and the Soviets had signed a non-aggression agreement. Latvia fell within the Soviet sphere of influence, under the terms of a secret amendment attached to this Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and amidst mounting pressure a fraudulently-installed “People’s Assembly” was able to declare the country a Socialist Soviet Republic in 1940, paving the way for Soviet military occupation.

The Nazis in turn invaded Latvia in 1941, holding Riga until 1944, when the Soviets were able to push them back out. Latvians were persecuted and conscripted by both sides during the conflict, and feelings can run strong around events that for some are still within living memory.

It is heartening to see how much of Riga survived the destruction, given this history, yet a great deal was lost as well. Only one Latvian bicycle factory remained operational at the close of WWII: the Erenpreiss plant, in Riga. The Soviets nationalized the facility, rebranding its products under the Sarkanā Zvaigzne (Red Star) badge and ramping up production. Red Star bikes came to enjoy a stellar reputation of their own across the Soviet Union, and in 1960 the factory was able to churn out 183,000 bicycles. Unfortunately for the masses of Soviet cyclists, it was then decided that the Red Star