Fall down, Stand up.

Gorilla concepts often take their sweet time developing into full production because, as Schreier puts it, “we want to prove our capabilities in a professional sports environment and test our material under professional conditions.” To that end he has been a primary sponsor of track racer Barry Forde, maintaining a product feedback loop. “His legs crack every frame if he wants to,” Schreier marvels, adding that “the main goal” of his relationship with the Pan American and World Championship medalist from Barbados “is to make the stiffest possible frame for his track sprints.”

Schreier takes pride in knowing that the strength demanded by Forde ultimately benefits Gorilla riders who may be less competitive but no less demanding of their bikes. Bike messengers were a natural extension for the company from the outset; it was through their sponsorship of their hometown X-Days races that I first caught wind of them, and a year later they were sponsoring the Cycle Messenger World Championships in Toronto. Gorilla has also thrown their stock behind the Paris-based DTGP bike polo team, who dutifully put their signature red, white and blue frames through the paces of the sport’s mallet-cracking rigors. That relationship in turn has led to investment in a line of wheelsets, lacing 48-hole Miche Primato hubs to stiff Le Lama mountain bike rims, developed specifically for urban freestyle and bike polo.

For 2010 the company officially launched the Kilroy, a freestyle frame that Schreier considers to be emblematic of the company’s reverence for cycling’s tradition and dedication to its evolution. Like Forde’s track frames, the Kilroy was borne of product testing that began more than a year ago and went through a long process of design and redesign—primarily via the snap, crackle and pop of prototype frames at the hands of Staten Island-based rider Edward “Wonka” LaForte.

“We broke a lot of frames,” Schreier recalls of the R&D phase. “We couldn’t test the strength of the frame in the laboratory, because there is no machine that does what these guys do on those bikes. The tests that Wonka ran lead to the conclusion that we had to manufacture a tube set just for this frame, with particular reinforced parts to absorb and handle the stress of the jumps.”

For Schreier, trial and error is integral to the process that he hopes ensures Gorilla’s association with quality. All aspects of development have been paced and thorough, from the “field research” of the startup days finding the right fabrication partner (“thousands of kilometers on Italian highways, nights in motels, and bad meals along the road”) to LaForte’s product testing. Since Gorilla frames come with a 10-year warranty, there is no shame in a broken frame during the research phase; the first Kilroy prototype proudly adorns the wall of the company’s offices, the cracked headtube joint highlighted by a heart drawn in Sharpie.

After consulting with the engineers at Columbus’s plant outside of Milan, what Gorilla ultimately settled on, “in order to avoid very thick and heavy tubes and gain in strength nevertheless,” was a new geometry of curved seat- and downtubes, made from a different alloy. The Kilroy is “the first freestyle frame in Niobium steel,” Schreier beams about the tubeset, touted as a special blend of manganese, chrome, nickel, molybdenum and niobium “designed to provide superior mechanical properties.”

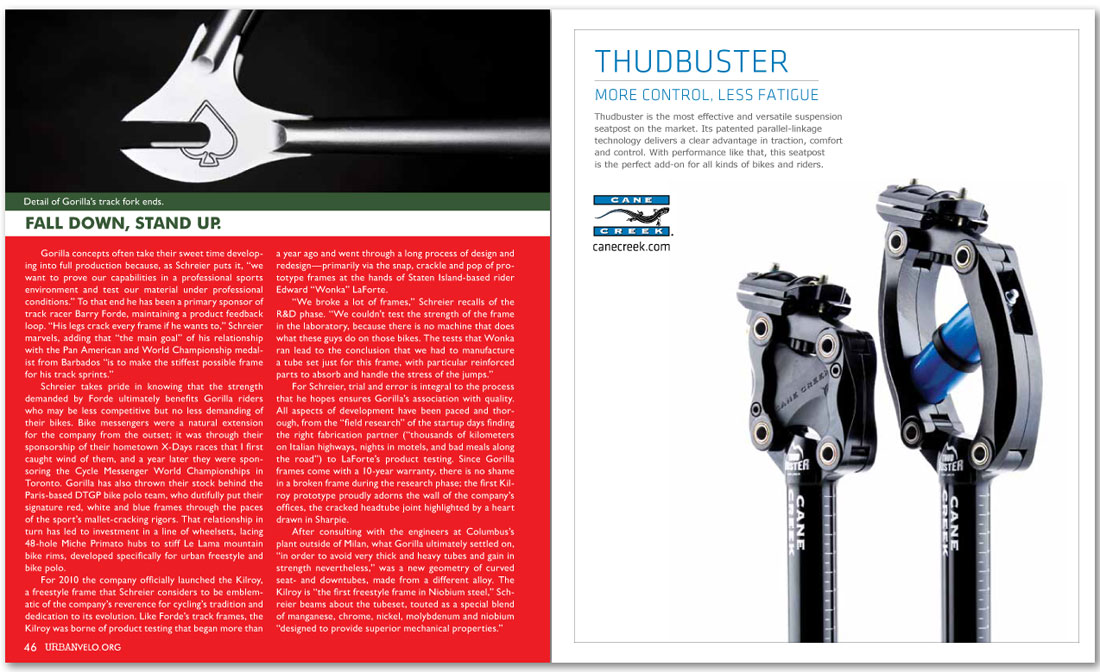

Cane Creek