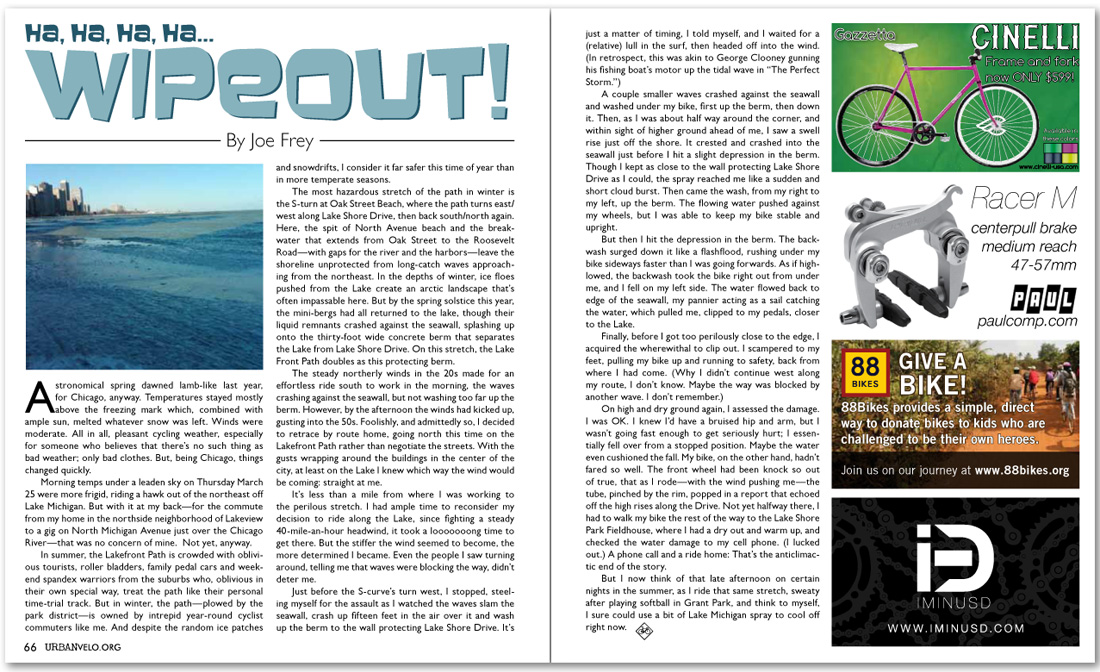

Ha, Ha, Ha, Ha... Wipeout!

By Joe Frey

Astronomical spring dawned lamb-like last year, for Chicago, anyway. Temperatures stayed mostly above the freezing mark which, combined with ample sun, melted whatever snow was left. Winds were moderate. All in all, pleasant cycling weather, especially for someone who believes that there’s no such thing as bad weather; only bad clothes. But, being Chicago, things changed quickly.

Morning temps under a leaden sky on Thursday March 25 were more frigid, riding a hawk out of the northeast off Lake Michigan. But with it at my back—for the commute from my home in the northside neighborhood of Lakeview to a gig on North Michigan Avenue just over the Chicago River—that was no concern of mine. Not yet, anyway.

In summer, the Lakefront Path is crowded with oblivious tourists, roller bladders, family pedal cars and weekend spandex warriors from the suburbs who, oblivious in their own special way, treat the path like their personal time-trial track. But in winter, the path—plowed by the park district—is owned by intrepid year-round cyclist commuters like me. And despite the random ice patches and snowdrifts, I consider it far safer this time of year than in more temperate seasons.

The most hazardous stretch of the path in winter is the S-turn at Oak Street Beach, where the path turns east/west along Lake Shore Drive, then back south/north again. Here, the spit of North Avenue beach and the breakwater that extends from Oak Street to the Roosevelt Road—with gaps for the river and the harbors—leave the shoreline unprotected from long-catch waves approaching from the northeast. In the depths of winter, ice floes pushed from the Lake create an arctic landscape that’s often impassable here. But by the spring solstice this year, the mini-bergs had all returned to the lake, though their liquid remnants crashed against the seawall, splashing up onto the thirty-foot wide concrete berm that separates the Lake from Lake Shore Drive. On this stretch, the Lake Front Path doubles as this protecting berm.

The steady northerly winds in the 20s made for an effortless ride south to work in the morning, the waves crashing against the seawall, but not washing too far up the berm. However, by the afternoon the winds had kicked up, gusting into the 50s. Foolishly, and admittedly so, I decided to retrace by route home, going north this time on the Lakefront Path rather than negotiate the streets. With the gusts wrapping around the buildings in the center of the city, at least on the Lake I knew which way the wind would be coming: straight at me.

It’s less than a mile from where I was working to the perilous stretch. I had ample time to reconsider my decision to ride along the Lake, since fighting a steady 40-mile-an-hour headwind, it took a looooooong time to get there. But the stiffer the wind seemed to become, the more determined I became. Even the people I saw turning around, telling me that waves were blocking the way, didn’t deter me.

Just before the S-curve’s turn west, I stopped, steeling myself for the assault as I watched the waves slam the seawall, crash up fifteen feet in the air over it and wash up the berm to the wall protecting Lake Shore Drive. It’s just a matter of timing, I told myself, and I waited for a (relative) lull in the surf, then headed off into the wind. (In retrospect, this was akin to George Clooney gunning his fishing boat’s motor up the tidal wave in “The Perfect Storm.”)

A couple smaller waves crashed against the seawall and washed under my bike, first up the berm, then down it. Then, as I was about half way around the corner, and within sight of higher ground ahead of me, I saw a swell rise just off the shore. It crested and crashed into the seawall just before I hit a slight depression in the berm. Though I kept as close to the wall protecting Lake Shore Drive as I could, the spray reached me like a sudden and short cloud burst. Then came the wash, from my right to my left, up the berm. The flowing water pushed against my wheels, but I was able to keep my bike stable and upright.

But then I hit the depression in the berm. The backwash surged down it like a flashflood, rushing under my bike sideways faster than I was going forwards. As if high-lowed, the backwash took the bike right out from under me, and I fell on my left side. The water flowed back to edge of the seawall, my pannier acting as a sail catching the water, which pulled me, clipped to my pedals, closer to the Lake.

Finally, before I got too perilously close to the edge, I acquired the wherewithal to clip out. I scampered to my feet, pulling my bike up and running to safety, back from where I had come. (Why I didn’t continue west along my route, I don’t know. Maybe the way was blocked by another wave. I don’t remember.)

On high and dry ground again, I assessed the damage. I was OK. I knew I’d have a bruised hip and arm, but I wasn’t going fast enough to get seriously hurt; I essentially fell over from a stopped position. Maybe the water even cushioned the fall. My bike, on the other hand, hadn’t fared so well. The front wheel had been knock so out of true, that as I rode—with the wind pushing me—the tube, pinched by the rim, popped in a report that echoed off the high rises along the Drive. Not yet halfway there, I had to walk my bike the rest of the way to the Lake Shore Park Fieldhouse, where I had a dry out and warm up, and checked the water damage to my cell phone. (I lucked out.) A phone call and a ride home: That’s the anticlimactic end of the story.

But I now think of that late afternoon on certain nights in the summer, as I ride that same stretch, sweaty after playing softball in Grant Park, and think to myself, I sure could use a bit of Lake Michigan spray to cool off right now.