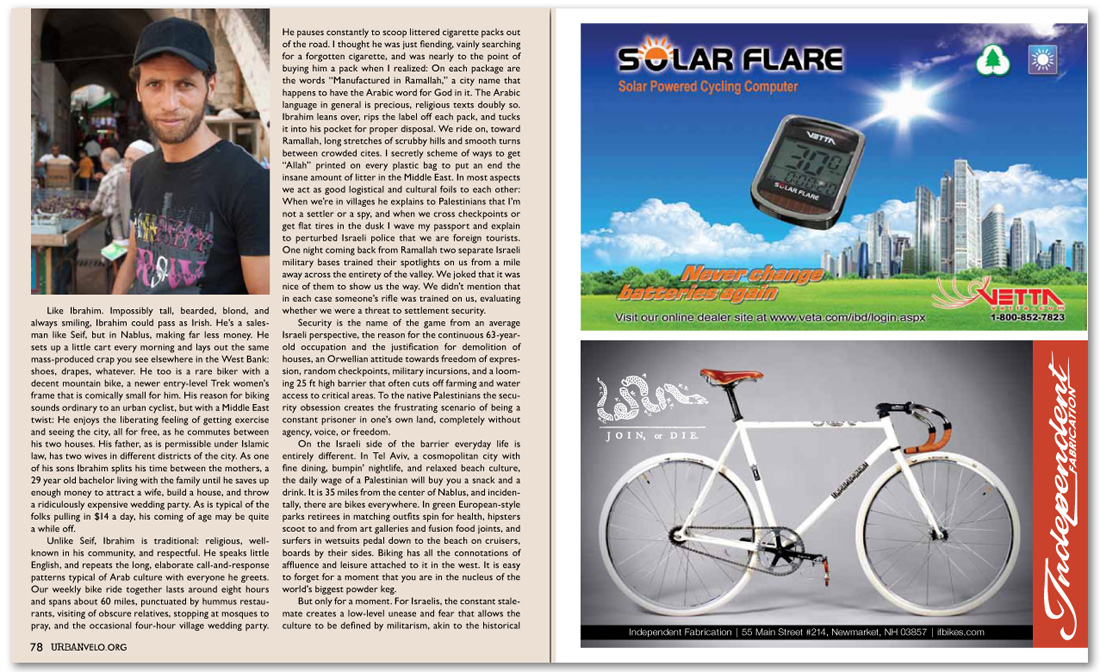

Like Ibrahim. Impossibly tall, bearded, blond, and always smiling, Ibrahim could pass as Irish. He’s a salesman like Seif, but in Nablus, making far less money. He sets up a little cart every morning and lays out the same mass-produced crap you see elsewhere in the West Bank: shoes, drapes, whatever. He too is a rare biker with a decent mountain bike, a newer entry-level Trek women’s frame that is comically small for him. His reason for biking sounds ordinary to an urban cyclist, but with a Middle East twist: He enjoys the liberating feeling of getting exercise and seeing the city, all for free, as he commutes between his two houses. His father, as is permissible under Islamic law, has two wives in different districts of the city. As one of his sons Ibrahim splits his time between the mothers, a 29 year old bachelor living with the family until he saves up enough money to attract a wife, build a house, and throw a ridiculously expensive wedding party. As is typical of the folks pulling in $14 a day, his coming of age may be quite a while off.

Unlike Seif, Ibrahim is traditional: religious, well-known in his community, and respectful. He speaks little English, and repeats the long, elaborate call-and-response patterns typical of Arab culture with everyone he greets. Our weekly bike ride together lasts around eight hours and spans about 60 miles, punctuated by hummus restaurants, visiting of obscure relatives, stopping at mosques to pray, and the occasional four-hour village wedding party. He pauses constantly to scoop littered cigarette packs out of the road. I thought he was just fiending, vainly searching for a forgotten cigarette, and was nearly to the point of buying him a pack when I realized: On each package are the words “Manufactured in Ramallah,” a city name that happens to have the Arabic word for God in it. The Arabic language in general is precious, religious texts doubly so. Ibrahim leans over, rips the label off each pack, and tucks it into his pocket for proper disposal. We ride on, toward Ramallah, long stretches of scrubby hills and smooth turns between crowded cites. I secretly scheme of ways to get “Allah” printed on every plastic bag to put an end the insane amount of litter in the Middle East. In most aspects we act as good logistical and cultural foils to each other: When we’re in villages he explains to Palestinians that I’m not a settler or a spy, and when we cross checkpoints or get flat tires in the dusk I wave my passport and explain to perturbed Israeli police that we are foreign tourists. One night coming back from Ramallah two separate Israeli military bases trained their spotlights on us from a mile away across the entirety of the valley. We joked that it was nice of them to show us the way. We didn’t mention that in each case someone’s rifle was trained on us, evaluating whether we were a threat to settlement security.

Security is the name of the game from an average Israeli perspective, the reason for the continuous 63-year-old occupation and the justification for demolition of houses, an Orwellian attitude towards freedom of expression, random checkpoints, military incursions, and a looming 25 ft high barrier that often cuts off farming and water access to critical areas. To the native Palestinians the security obsession creates the frustrating scenario of being a constant prisoner in one’s own land, completely without agency, voice, or freedom.

On the Israeli side of the barrier everyday life is entirely different. In Tel Aviv, a cosmopolitan city with fine dining, bumpin’ nightlife, and relaxed beach culture, the daily wage of a Palestinian will buy you a snack and a drink. It is 35 miles from the center of Nablus, and incidentally, there are bikes everywhere. In green European-style parks retirees in matching outfits spin for health, hipsters scoot to and from art galleries and fusion food joints, and surfers in wetsuits pedal down to the beach on cruisers, boards by their sides. Biking has all the connotations of affluence and leisure attached to it in the west. It is easy to forget for a moment that you are in the nucleus of the world’s biggest powder keg.

But only for a moment. For Israelis, the constant stalemate creates a low-level unease and fear that allows the culture to be defined by militarism, akin to the historical